Monochromator principles

of operation

Although many detailed variations are possible, most monochromators are of the same basic

design, which is generally known as the Czerny-Turner configuration, and ours is no exception.

Its operation is quite easy

to understand, but this topic is

not well covered by

standard optical texts, and we therefore

give a basic description here. This description will also explain

the particular features of our

own design, and will also explain

the very important interaction between bandwidth and optical throughput,

which our real-time slit width control system

can fully exploit. The standard Czerny-Turner configuration is shown below.

Light from an appropriate source (a xenon arc in our case) is

focussed onto an input slit, and light passing

through this slit is collimated by a concave mirror, which also reflects

it onto a diffraction grating. The grating in turn directs the

light onto a second concave mirror, which reflects

and focusses it onto an

exit slit before it leaves the instrument. Mirrors are used rather than lenses

because they do not introduce any chromatic

aberration, but they do introduce other aberrations which limit the resolution of the

instrument, as will be discussed shortly. Since the redirection

of the light

beam by the grating is actually

a diffraction rather than an ordinary

reflection, the grating disperses the beam, i.e.

different wavelengths leave the grating

at different angles. By rotating the grating about

its central axis, we can

vary the range of wavelengths which can be

reflected and focussed by the second mirror onto

the exit slit.

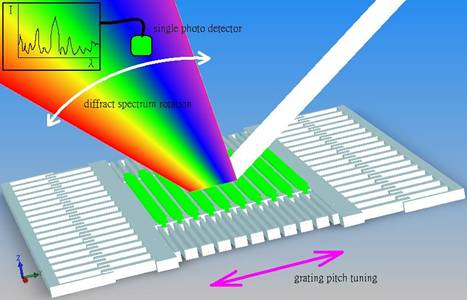

Standard Czerny-Turner configuration

The figure below

shows how a reflective grating works. This is

a horizontal section through the grating,

which resembles a saw blade. Viewed

face on, the "teeth"

are actually grooves, and the two

slits in the instrument are

parallel with them. (Slits can

be used rather

than circular apertures because the grating disperses

light only in the horizontal direction, so by lengthening the apertures in the vertical direction we can get

more light through the instrument without losing any resolution).

Imagine a light beam arriving at

a direction perpendicular

to the grating. If the grating

just acted as a mirror, the beam

would be reflected straight back again, and

indeed, some proportion of the

light is reflected in this way, but in this

case it is

referred to as the zero-order diffracted

beam. However, the grooves are shaped so that

most of the light leaves the

grating at a different angle, corresponding to the first-order diffracted

beam. This angle corresponds to the one where

reflections f rom adjacent teeth give optical patch

length differences of exactly one

wavelength. Since the angle is

therefore wavelength-dependent, the diffracted beam actually forms a spectrum, from which we can

select the required wavelengths by focussing them onto the exit slit.

Principle of operation of reflection

grating

In the Czerny-Turner configuration, this is done

by rotating the grating so that

the required wavelength is always

reflected at the same angle.

This means that the angle

of the incoming

light also changes, but that

doesn't have any major impact apart from making

the calculations somewhat more interesting. The angles of

the incoming and outgoing beams

are conventionally referred

to as a and b respectively, and although they both

change when the grating is

rotated, the difference between them, conventionally referred to as D, remains constant. Note that a and b are both measured with

respect to the grating normal, and they will

be of opposite

signs if they are on opposite sides of the

grating normal.

The basic grating

equation is given by:

![]()

where l is the

wavelength in nm, k is the diffraction order and n is

the number of lines per mm for the grating.

This can be rearranged in terms of the

wavelength to give:

For a given instrument the deviation D is fixed and

given by:

![]()

so we can

express b in terms of

D and a and then solve for

a to obtain:

For reference, n for our standard grating is 1200 lines/mm, k is always 1 (i.e. first-order

diffraction) and D in our instrument is 20 degrees. The sensitivity of the electrical

input which controls the grating

angle is 0.25 volts per degree. Users who wish

to make their own arrangements for driving the

monochromator can therefore substitute these values

into equation (4) in order to calculate the appropriate drive voltage for a given

wavelength. However, users who also

have our microprocessor control box do not

need to become involved with any

of this, as the microprocessor performs these calculations itself, so the

required wavelengths can be specified

directly.

There are also maxima corresponding to path length differences of two or

more wavelengths, giving second- and other

higher-order diffracted beams (this series continues

up to the maximum possible diffracted angle of 90 degrees),

and there is another complete

set of diffracted beams at the

same angles on the other side

of the incoming

beam. However, by appropriately shaping the grooves in the grating, which

is termed blazing, it is

possible to direct most of the diffracted

light into a particular ONE of these several destinations, over a reasonably wide range of wavelengths.

The wavelength at which this

occurs most efficiently is known as the

blaze wavelength, and we use a grating with a blaze wavelength of 400nm in order to obtain highest grating efficiency (of around 70% into

the required first order diffracted

beam) in the near UV, for

optimum results with indicators such as fura-2 and indo-1. However,

the efficiency is still above

50% over most of the visible spectrum

too.

Although a number of

other configurations have been described,

nothing else seems able to beat

the performance of the Czerny-Turner, particularly in respect of the (for

biological fluorescence applications)

requirement for high optical throughput,

which we discuss below. In our opinion the

only viable alternative is one in which the

grating itself is concave, so

that the two concave mirrors

are no longer required. However, the substantially

higher cost of such gratings (which must be

custom designed) makes the instrument more expensive overall. Conventional plane gratings are

much cheaper, and our suppliers can

provide gratings with almost any

required characteristics at the same

relatively low cost. The standard grating we supply

has 1200 line lines/mm, blazed

at 400nm, since we believe it

represents the best overall compromise

for this type of instrument. However, just about any

other required characteristic can be supplied to special order.

Grating